You are a recipient of Coucou Postale, a postcard series designed to engage and delight readers through stories and art using good-old fashioned mail and the magic of the Internet.

Achillea millefolium — Carmarthenshire, Wales, 2018.

By now, it’s clear that plant lore is often rooted in stories of gallantry and loss. But blooms can help us, too. Consider Achillea millefolium.

Until recently, Achillea millefolium, or yarrow as it is commonly known, has been relegated to the roadside, but it holds an esteemed place in folk medicine. Part of its name, Achillea, comes from the name of the Greek hero, Achilles, who Chiron the centaur taught of its healing properties. Achilles was a warrior, and Chiron, a scholar of medicine and the stars, anticipated the wounds this warrior would encounter. Among other remedies, he showed Achilles how to apply an ointment of yarrow to stanch bleeding. Years ago, I remember buying a yarrow cream to mend my wounds. This act was a testament to how the stories of humans and plants are intertwined, but also their power to heal in any time.

Ancient Greeks weren’t the only people to recognize this plant’s potency. Native people of the Americas believed yarrow to be “life medicine.” From treating headaches and fevers to aiding in sleep, yarrow was an integral part of their daily lives. Even in my motherland, the United Kingdom, yarrow plays a visionary role in Gallic lore: a leaf of yarrow across the eye was believed to bestow second sight.

Far away in space and time, a similar concept exists in China where practitioners of the I Ching have long used dried yarrow stalks in this millennia-old divination ritual. The diviner collects 50 yarrow stalks locally, cleans and lacquers them, and uses them in an intricate process of foretelling a path. Finding local yarrow matters. In Chinese traditional medicine, practitioners believe that the qi (life essence) of the yarrow will be more in-tune with the diviner if collected locally. What seems key to all of this is the relationships humans have cultivated with plants. It’s not that they saw them as saviors, but companions to a better way of living and aid in seeing the world.

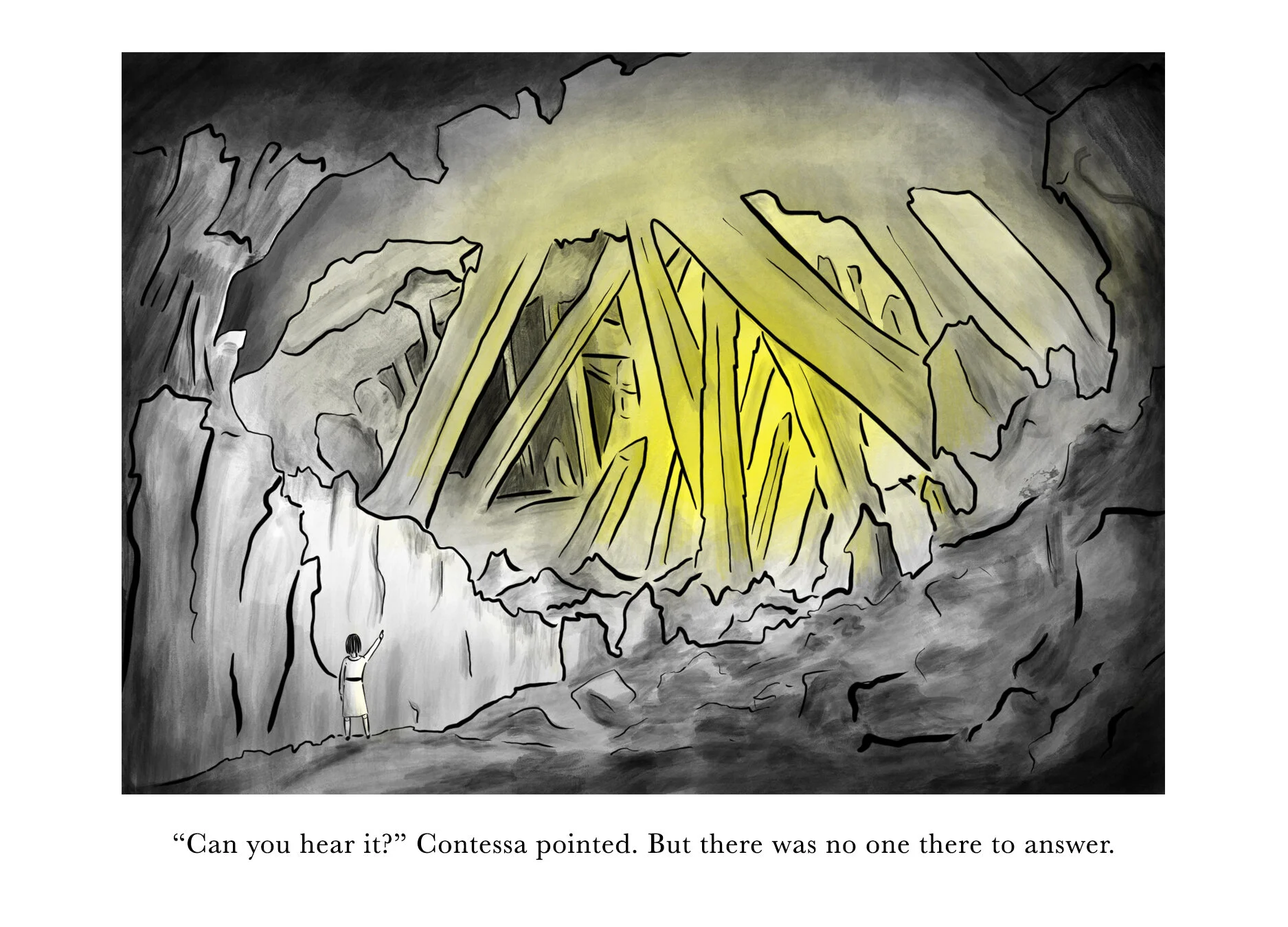

Years after I bought the yarrow ointment, I stayed in a lovingly restored cottage from 1755 in Carmarthenshire, Wales. Carmarthenshire is considered the birthplace of Merlin, the magical sage who added Arthur throughout his travails. The area, and all of Wales for that matter, seemed to brim with a kind of whimsy only a place still rooted in legends could evoke. And where there are rich legends, there is also a fierce appreciation for the natural world.

A long lane led up to the house, and every evening, I would take in the long light. Summer was close to ending. The earth turned golden. I would miss the blackberries, now green but hinting at the sweetness to come, and this thought disappointed me. Then I saw the yarrow. Now, I do not have a favorite flower or plant, but there are those plants that touch something deep within you. Here was yarrow, which I had seen at this point in various settings around the world, but it was as though I was seeing it for the first time. In the dusk, it seemed as though the most gentle of pinks infused the bloom, a magical talisman aglow from setting sun.

I cut the stem and took it home. There was no bleeding to staunch that evening but it certainly mended a broken heart.